SAMI

Published:2020-03-17 08:21:42 BdST

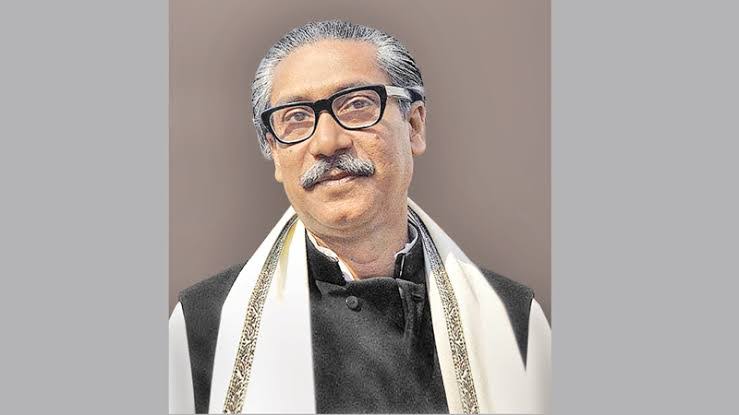

A Tireless Statesman

Pranab Mukherjee

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was born on 17th March 1920 in Tungipara in the district of Gopalganj in undivided Bengal. His father’s name was Sheikh Lutfar Rahman. His paternal grandfather’s younger brother, Khanshaheb Sheikh Abdur Rashid, established a Middle English (ME) school in Gopalganj. At that time, it was the only place to learn English in that region.

The Sheikh family was wealthy at one time, but lost nearly everything because of a criminal case lodged by the rulers of that time. From Mujib’s grandfather’s time, the Sheikh family began studying English. His father was in highschool when his grandfather passed away. Mujib was married when he was only twelve years old. His wife’s nickname was Renu. When Renu’s father passed away, her grandfather called in Mujib’s father and told him that his eldest son should marry one of his granddaughters, because he wanted to leave all his property to his two granddaughters. Renu’s grandfather was Mujib’s father’s paternal uncle. In order to obey the directive of elders, Mujib’s marriage to Renu was registered. Mujib was twelve years old at that time. Renu was three or four. After the death of Renu’s grandfather, Renu was also brought up by Mujib’s mother.

In 1938, Mujib suddenly fell ill and his treatment lasted nearly two years. In 1936, when he was in Class Seven, Mujib developed glaucoma. His studies were repeatedly interrupted due to illness. He gained admission to Gopalganj Mission School again in 1937. In 1938, when Mujib was still a student, the then first premier of Bengal, AK Fazlul Huq and Labor Minister Shaheed Suhrawardy visited Gopalganj.

As he was assembling a group of volunteers for the occasion, Mujib noticed that the Hindu boys were slowly distancing themselves. This was because the leaders of the Hindu community were going to the students’ houses and telling them that congress was unhappy with the fact that Huq Shaheb and Suhrawardy had formed the cabinet with the help of the Muslim League. Therefore, the Hindu students didn’t want to cooperate.

When Suhrawardy went to visit the Mission School, he was introduced to Mujib, who was one of the students. Mujib informed him that there were no chapters of the Chhatra League or Muslim League in their area. Suhrawardy noted this down in his notebook, along with Mujib’s name and contact information and told him to keep in touch. Mujib and Suhrawardy met again in 1939 when Mujib proposed the formation of Chhatra League in Gopalganj. In this way, Bangabandhu slowly entered politics. At that time, his father was the chief administrative officer of the Madaripur Subdivision.

In 1941, right before his Matric exams, Mujib became seriously ill, his fever reaching 104 degrees. His results weren’t as good as he had expected since he had to take the exams while he was ill. During that period, Mujib became heavily involved in politics. In his own words, he said: “I attended meetings, gave speeches. I didn’t take part in sports. Just Muslim league and Chhatra League. Pakistan had to be realized. Otherwise Muslims had no way of surviving. Whatever was written in the newspaper Azad all seemed true.” (Unfinished Memoirs)

After matriculation, Mujib joined Islamia College. Under his leadership, the college became the heart and soul of Bangladesh’s student revolution. Mujib had been deeply involved in student politics all along. Later on in his political life, Bangabandhu was the favorite of students and the youth. In fact, even in those fiery days of 1971, when East Pakistan was in turmoil, the four student leaders—they were called the four Khalifas (Abdur Rab, Shahjahan Siraj, Nur E Alam Siddiqui and Abdur Razzak)—could always be found at his side. Mujib would consult with them on many important decisions. The impact of Chhatra League on that mass movement was immeasurable.

In an essay about Mujib it was said that in the thousand year history of Bengal, his was a name spelled out by the stars, which would continue to glow with its own radiance. In fact, he worked tirelessly from the mid 30s for the establishment of Pakistan, and when East Pakistan was created, his struggles did not cease.

Mujib believed that Pakistan was created with a set of specific goals and ideals in mind. Khwaja Nazimuddin’s family played a pioneering role in the Muslim movement. Khwaja Nazimuddin was the Prime Minister of Bengal in the 40s and became Chief Minister when East Pakistan was created. He was also the Governor General of undivided Pakistan.

Khwaja Shaheb was then the Prime Minister of East Pakistan. In the 1937 elections, eleven members of the Khwaja family became MLAs. In 1943, when Khwaja Nazimuddin became Prime Minister, he made his younger brother Khwaja Shahabuddin the Minister of Commerce, Labour and Industry. The famine had begun at that time. Thousands of people were leaving the villages for the cities. There was no food to be found in rural Bengal. The British government had confiscated all the boats for its war effort and had reserved all the food grains for soldiers.

On the issue of how to improve relations between Hindus and Muslims, in his autobiography, Mujib referred to Shubhash Chandra and Chittaranjan Das, writing: If the leaders and activists of Bengal’s revolutionary movement, who had sacrificed their all for their country, had raised awareness among the masses regarding harmony between Hindus and Muslims in general, and against Hindu traders, moneylenders and landlords and tenure-holders in particular, then the Hindus-Muslim conflict created in undivided Bengal, which helped give birth to Pakistan, would not have been possible.

Moulana Azad also wrote in his book, India Wins Freedom, that among all the leaders of congress only Chittaranjan Das realized that Muslims who had fallen behind should be given appointments on a priority basis if the greater Muslim community was to be included in congress. And not just in theory, but also in practice, he reserved 80% of new positions in the Kolkata Corporation for Muslims.

However, Mujib’s political mentor Suhrawardy fell victim to Muslim League’s internal conspiracies during partition in 1947, even though under his leadership the Muslim League won 119 of the 124 seats reserved for Muslims in the general elections of 1946. Under the leadership of Fazlul Huq, the Krishak Praja Party won four seats. In spite of this, Muslim League supremo Suhrawardy was removed and Khwaja Nazimuddin was appointed Prime Minister of East Pakistan. Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar was the Muslim League observer at the meeting where Khwaja Nazimuddin was elected the leader of East Pakistan. He was a close confidante of Jinnah.

The Pakistan that Mujib worked so hard to create—going from village to village generating publicity and breathing life into the Muslim League and Chhatra League; even during the 1947 referendum, travelling by steamer to Sylhet with the help of businessman Randaprasad Chowdhury to promote in favor of Pakistan, in the end achieving the inclusion of Srihatta—gradually, intense disagreements arose between that very same Mujib and the Muslim League leadership. He began to oppose various policies and their applications. Because of this, he was imprisoned shortly after liberation for criticizing and opposing government policies at different times. If the 9 months in 1971 are included, then Mujib’s total period of imprisonment comes to 3,053 days. He wrote his Unfinished Memoirs while in jail and it was published 29 years after his death. In the introduction to Unfinished Memoirs, the Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina wrote that she received the four notebooks around the same time as the horrific grenade attack of 21 August 2004 at the Awami League rally held on Bangabandhu Avenue, which was intended to end her life and killed 24 League leaders. One of her cousins gave the notebooks to her; they had been found inside the desk drawer of Bangabandhu’s nephew, and Banglar Bani editor, Sheikh Fazlul Haque Mani’s office. Perhaps Mujib had given Mani the notebooks to have them typed up. On 25th August 1975, the assailants attacked Sheikh Mani’s house as well as that of Mujib; he and his entire family were also killed. Unfinished Memoirs was compiled from those notebooks.

It would be next to impossible to make any general assessments of the significant, industrious life of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, which was an indicator of his patience, attitude, commitment and infinite self-control. On the night of 25th March 1971, the Pakistan Army arrested Mujib and took him to Karachi as a prisoner. The picture of him with two military officers, taken at the Karachi airport, was published in various newspapers around the world. From then on, Mujib was in the Mianwali jail in West Pakistan, near Rawalpindi. From 25th March 1971 to 9th January 1972, he received no news of what was happening in the world. During this time, he was subjected to extreme heat and cold for nearly nine months in order to create physical and mental stress. He was given only one blanket to ward off the cold and was not permitted any medical check-ups. As a military officer, the jail governor would visit him from time to time. He received no news of the war.

While in jail, by observing the increased activity of war planes in the sky and listening to the internal conversations of the military guards, Mujib gleaned that a war had perhaps broken out between India and Pakistan. He was imprisoned in that jail until 26th December. Then, on the last night, the jail governor made him lie on some hay in the back of a truck and drove him through mountains and forests, in the pouring rain, to some unknown location. All the man said was, “Your life was in danger in jail. I have been given the responsibility of taking you to a safe location.” Mujib was provided no further information. But he was taken to a nice, clean bungalow (which was the jailer’s official residence). He was also given the opportunity to shower and provided warm clothes, a shaving kit and other amenities, of which he was deprived for nine months. But Mujib was still not given access to any newspapers or the radio, television or telephone. Five days later, that is, on the afternoon of 1st January 1972, two military officers took him in a staff car to another bungalow, which was located 25 kilometers away from Rawalpindi. There, the then-president of Pakistan, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto met with him in the afternoon. Bhutto informed Mujib that he was the president and needed Mujib’s help. During the few days between 1st and 8th January, Bhutto spoke to him at various times and pressured Mujib to sign a joint statement. He showed Mujib many drafts. Mujib asked right at the beginning whether he had been freed from prison or simply moved from Mianwali Jail to another prison, one in which living was comfortable and easy to bear. It was there that he had the opportunity to read the newspaper. But the papers which reached him had various news items blacked out. As it happens, one day a copy of Time magazine which had no redactions found its way into Mujib’s hands. In it, he found an article discussing the problems Sheikh Mujib, as Bangladesh’s head of state, might focus on in the coming days. Moreover, a question was raised in an editorial: where was Mujib? If he was alive, how was the head of state of a country being kept prisoner in a Pakistani jail? Mujib found discussions on many other issues in the magazine.

Meanwhile, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto made repeated appeals to Mujib to establish a relationship between Pakistan and Bangladesh. A relationship that would keep Pakistan undivided. Mujib simply informed Bhutto that he would not be able to say anything to him without first conferring with the people of his country. In the end, a frustrated Bhutto decided to send Mujib to Britain. In the middle of the night on 8th January 1972, a special Pak Airlines plane flew Mujib, its sole passenger, to London’s Heathrow airport. When he landed at Heathrow, the local time was 6:30 am. Heathrow airport authorities had been previously notified by the Pakistan government that an unscheduled flight carrying Mujib was on its way to London, so that it would be allowed to land, and the British foreign ministry and prime minister’s office were informed. The British secret service agents took Mujib directly from Heathrow to Claridge's Hotel. As soon as the news spread, Bengalis residing in London went to the hotel to meet Mujib, each relaying his or her own version of events to him. Mujib received news of Bangladesh, though Bhutto had already informed him in passing that all his family members were alive, even his parents.

Discussions, writings and research on Bangabandhu continues, and will do so for years to come. I want to end this article with a comment made by Bangabandhu in 1973, in a notebook written in his own hand; a complete introduction to him can be found in this quote: “As a human being, I think about all of humanity. As a Bengali, all that which is related to Bengalis concerns me deeply. The source of this everlasting bond is love—enduring love—a love that gives meaning to my politics and my existence.”

Pranab Mukherjee is a former President of India

Unauthorized use or reproduction of The Finance Today content for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited.