Syed Badrul Ahsan

Published:2020-08-15 21:45:58 BdST

‘I am the government’

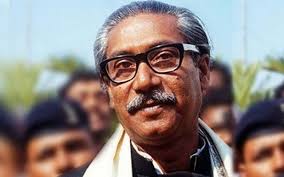

Arriving in Rawalpindi, a couple of days after the withdrawal of the Agartala Conspiracy Case and the release of all the accused in the case in February 1969, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was asked by journalists how he felt being a free man. In West Pakistan to take part in the Round Table Conference called by President Mohammad Ayub Khan, his long-time tormentor, Bangabandhu had a cryptic response: 'Yesterday a traitor, today a hero.'

He could not have been more right. Where the regime had gone out of its way to portray Bangabandhu as a traitor, especially since he first put forth his Six Point programme of regional autonomy in February 1966, it was his fellow Bengalis to whom he had emerged as a heroic figure. In effect, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman rose to the heights, as the leading voice of Bengali aspirations, when a grateful nation --- grateful for the consistent struggle he had put up in defence of their rights --- honoured him as Bangabandhu by acclamation. He was thus in Rawalpindi not merely as Sheikh Mujib but as de facto leader of his people, as a politician who would make a difference in the region as a whole.

That Sheikh Mujibur Rahman would make a difference had always been known, given his determined struggle to secure political and economic rights for his people. It was not for nothing that he once quipped he could smell the jute and tea of East Bengal on the streets of West Pakistan. It was sarcasm grounded on reality; and the reality was one of systemic exploitation of East Bengal. In those Six Points were inherent his recipe for a turnaround, for his fellow Bengalis to assert their rights, be they within the concept of the Pakistan state or outside it. As he often told people close to him, the Six Points were but a bridge to a single point, freedom. And yet he was shrewd enough as a politician not to be labelled as a secessionist. He would wait, give the ruling coterie in Rawalpindi enough rope to hang itself.

It was Bangabandhu's supreme confidence, in himself and in his people, that was to change the political landscape in our part of the world. The ten years of Ayub Khan did little to silence him. Prior to that, the machinations of the West Pakistani ruling class were unable to curb his growing nationalistic tendencies. Having worked for the movement for Pakistan in the 1940s, he came round to the realisation that the state Mohammad Ali Jinnah had built was not working --- and would not work --- to specifications. The ruling classes needed to be shamed, to be told the truth to their faces. It was thus that in Karachi, in company with Sher-e-Bangla AK Fazlul Huq, he was bold enough to ask Prime Minister Mohammad Ali Bogra why he was being rude to the veteran leader.

Mujib was not to be intimidated by power. He was there to speak truth to power, which was reason why his tormentors considered it safe to put him away. Prison, as he was fond of saying, was his second home. It was those long stretches of incarceration that added increasing substance and quality to his politics, that honed his skills to engage the civil-military bureaucracy in political battle. His belief in the future was grounded on conviction. During the Agartala trial, he told a foreign newsman, 'You know, they can't keep me here for more than six months.' He was on trial on charges of treason and yet that steely determination to be the arbiter of his people's destiny defined him in court. 'Anyone who wishes to live in Bangladesh will have to talk to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman,' said he, referring to himself in the third person. In the end, everyone did talk to him.

Bangabandhu was that rare politician who saw little reason for political compromise when the priority was a fulfillment of national aspirations. In early 1964, soon after Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy's death in Beirut in December of the previous year, he considered it proper for the Awami League not to remain part of the opposition National Democratic Front any longer. Mujib was a man of action and was therefore not willing to bind himself in the fetters set by politicians who did not have much of a good record in the country. Besides, growing increasingly radical and free of Suhrawardy's politics of caution, he was ready to take his party on to entirely different and more purposeful moorings. The upshot of it all was the resurgence of a political party ready to be more assertive than it had been thus far.

In the global community, Bangabandhu did not let misconceptions about Bangladesh go past him without a tough response. When Nigeria's Yakubu Gowon wondered if Pakistan should not have been broken, Bangabandhu quickly swatted him down. When Saudi Arabia's King Faisal grumbled about the weakening of the Islamic world with Bangladesh's separation from Pakistan, Bangabandhu queried him on where Riyadh was when Pakistan's soldiers were killing Bengali Muslims in occupied Bangladesh. His gratitude to Indira Gandhi notwithstanding, he nevertheless asked her bluntly when she would withdraw her soldiers from Bangladesh. Those soldiers were gone in March 1972.

It was Shonar Bangla, Golden Bengal, that was his dream. He spoke of his ambition, repeatedly: it was to have smiles bathe the faces of his impoverished countrymen. For Bangabandhu, the dignity of the citizen was but the dignity of the state, which is why when some of his cabinet colleagues, not quite happy with his decision to travel to Lahore for the Islamic summit in February 1974, requested him to consult his Indian counterpart, he had a blunt response. He was, he reminded them, the leader of an independent country, not the chieftain of a protectorate.

In that steamy March 1971 when a non-cooperation movement under his leadership was reinventing politics in Bangladesh, a foreign journalist was curious why he was challenging the authority of the government of Pakistan. Here is how Bangabandhu responded to the question: 'What do mean government? I am the government.' And indeed he was, in those twenty-five days when the state of Pakistan tottered and teetered on the brink of disaster. The disaster would happen in nine months and Mujib was making sure that the centre of the state could not hold, would fall apart. Asked for his opinion on a projected visit to Dhaka by a clearly nervous President Yahya Khan, he made it clear who called the shots. Yahya, he said, was welcome to visit Dhaka, for 'he will be our guest.'

It was supreme confidence at work. Back in March 1969, in the final days of the Ayub dispensation, he publicly asked the weakened field marshal to remove his 'patwari' Abdul Monem Khan from the governor's house. In July 1970, when Yahya Bakhtiar, who would later be attorney general in post-1971 Pakistan, expressed the fear at a dinner in Quetta that the Six Points would cause Pakistan's break-up, Bangabandhu came forth with a no-nonsense response: 'You have sucked our blood for twenty-three years; now you must face the music.'

Bangabandhu was keen that heritage not be tampered with. Never comfortable with the term 'East Pakistan', he consistently emphasized 'East Bengal' and 'Bengal' in his public pronouncements all through the 1950s and 1960s. As the Yahya regime prepared to dismantle the One Unit system in West Pakistan and restore the old provinces, Bangabandhu made known his idea about Pakistan's eastern province. Speaking at a memorial meeting in Dhaka on the occasion of Suhrawardy's death anniversary in December 1969, he made the emphatic statement that thenceforth East Pakistan would be rechristened as Bangladesh. An idea was thus born and a dream was about to take shape.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was, and is, Bangladesh's window to the world. Years of imprisonment only enhanced his resolve to transform the fate of his people. The Ayub Khan regime looked forward to his conviction in the Agartala case and subsequent execution or imprisonment for life. The Yahya Khan junta, committing the foul deed of having Bangabandhu flown to West Pakistan under arrest in 1971, made sure that a sentence of death was passed on him. One can be certain Bangabandhu remained undaunted. The mass upsurge of 1969 forced the regime to free him. In 1971, it was the collapse of Pakistan that set him free.

This morning, forty-five years after sinister conspiracy caused the life to go out of him and of his family, it is the sheer cross of tragedy and penance we as a nation continue to bear. That Bangabandhu died alone, that we were not there to save him, that criminality and bloody treason reigned supreme in the land for twenty-one years after he was done to death, is guilt we cannot absolve ourselves of. He was our voice in the world, our liberator. Not all our tears will wash away the stains of shame we continue to live with.

'Here was a Caesar. When comes such another?'

Shakespeare's question is ours too.

Unauthorized use or reproduction of The Finance Today content for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited.