Syed Badrul Ahsan

Published:2020-03-18 02:36:13 BdST

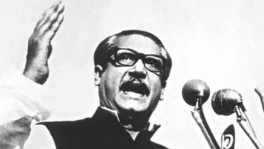

For Bangabandhu, prison was a second home

In his lifetime, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman often quipped that prison was his second home. The manner in which he often found himself in prison, the innumerable times when he was carted off to jail by successive Pakistani governments, are today the stuff of legend. Bangabandhu belonged to a class of political figures persecuted for their political beliefs endlessly by governments which saw in their activities a clear threat to their unfettered functioning.

The history of the Indian subcontinent is replete with tales of politicians languishing in prison thanks to the undemocratic nature of the regimes that had foisted themselves on society. Mahatma Gandhi, Subhas Chandra Bose and Jawaharlal Nehru went through endless ordeals as prisoners in the long period of British colonial rule in India. In post-1947 circumstances, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, known as the Frontier Gandhi, spent much of his adult life in Pakistan's prisons owing to his belief that the Pathans straddling Pakistan and Afghanistan needed to have their own state of Pakhtunistan. Likewise, the Sindhi nationalist G.M. Syed was kept in jail by Pakistan's governments. The poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz was sentenced to a jail term in the Rawalpindi conspiracy case of 1951. In later times, Khan Abdul Wali Khan, Abdus Samad Achakzai and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto served time in prison.

Bangabandhu's political experience in Pakistan was essentially a litany of the times he spent behind bars for his political beliefs. His career in prison began in 1948 when as a young politician he was carted off to jail. Following the dismissal of the Jukto Front government in East Bengal in 1954, he was arrested at Dhaka's Tejgaon airport on his arrival from Karachi. It would be the beginning of a protracted tale of suffering for him, especially with the imposition of martial law in Pakistan in October 1958. A few days after Iskandar Mirza and Ayub Khan rescinded civil liberties, abrogated the constitution and outlawed political parties, Bangabandhu was taken into custody. Not until fourteen months later, in 1961, through a directive of the higher judiciary, would he be released.

Nearly the entirety of the Ayub regime in Pakistan was spent in keeping Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in prison. It was particularly with the advent of Abdul Monem Khan, an unabashed Ayub loyalist appointed governor of East Pakistan by the regime, that Mujib's prison ordeals took on graver dimensions. He was arrested after nearly every public rally he addressed anywhere in the province. And every time he was placed under arrest, his lawyers moved the court and obtained bail for him. But just as one thought he was free, the authorities clamped a fresh new order of arrest on him. Physically it was taxing for Mujib, who was compelled to travel to the towns where the arrest notices had been served on him in order to seek bail.

Few were the years that Sheikh Mujibur Rahman spent in freedom with his family in Dhanmondi. His family always had a suitcase packed with his clothes ready in the event the police came with a fresh order of arrest for him. Governor Monem Khan went on record with his declaration that as long as he was in charge of East Pakistan, Mujib would not see the light of day. The future founder of Bangladesh was persecuted by Ayub Khan under the Elective Bodies' Disqualification Ordinance (EBDO). He was arrested in 1962 at about the same time that his political mentor Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy was taken under detention by the Ayub martial law regime. Mujib spent a good length of time in 1963 in jail. In 1964, as he campaigned for Fatima Jinnah in the run-up to presidential elections called by the regime, he was arrested again, to be released after the voting in January 1965.

But if these periods of detention were aimed at blocking Mujib from propagating his brand of democratic politics in Pakistan, those that were to come later were a clear threat to his very life. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman created a storm all over Pakistan when he announced his Six Point plan in Lahore on 5 February 1966. Almost immediately he was dubbed a secessionist, with President Ayub Khan threatening to employ the language of weapons against supporters of the Six Points. Not even Mujib's fellow opposition politicians came forward to support his demand. Foreign Minister Z.A. Bhutto challenged him to a public debate on the Six Points at Dhaka's Paltan Maidan but in the end did not turn up when Tajuddin Ahmad told him he was taking up the challenge on behalf of his leader.

Bangabandhu was arrested under the Defence of Pakistan Rules (DPR) on 8 May 1966. Obviously, the move was aimed at suppressing his campaign for the Six Points, which were a broad and radical plan envisioning regional autonomy for Pakistan's federating units but especially for East Pakistan. In December 1967, the Pakistan government revealed a conspiracy by a group of Bengali officers in the country's armed forces to bring about the separation of East Pakistan from the rest of the country. The next month, January 1968, it was announced that Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had been part of the conspiracy. Of the 35 Bengalis accused of planning the conspiracy, Mujib's name was placed at the top. Indeed, the case came to be officially known as 'State vs Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Others.' Mujib was moved from Dhaka central jail to maximum security imprisonment in the Dhaka cantonment.

The proceedings of the case commenced in June 1968 in the Dhaka cantonment before a Special Tribunal comprising Justice S.A. Rahman, a former chief justice of Pakistan, and Justices Mujibur Rahman Khan and Maksumul Hakim, Bengalis serving in the East Pakistan High Court. The apprehension in the public mind was that the plan of the regime was to find Mujib guilty of treason and either hang him or put him away for good under a life imprisonment. Unfortunately for the regime, a mass upsurge against the regime forced it to withdraw the case unconditionally and free Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his co-accused in February 1969. A day after his release, Mujib was bestowed the honour of Bangabandhu by a grateful Bengali nation.

If Bangabandhu had come through his Agartala case ordeal in safety, his next --- and final --- spell in prison was a clear portent of danger far greater than any earlier conceived by him and the people of Bangladesh. Elected leader of the majority party in Pakistan's first general election in December 1970, Bangabandhu was morally and politically placed to take charge as Pakistan's first elected prime minister. But the machinations of the Yahya Khan junta and Pakistan People's Party chairman Zulfikar Ali Bhutto led to a political crisis that was worsened by the launch of a genocide by the Pakistan army in East Pakistan in late March 1971.

Bangabandhu was arrested in the early hours of 26 March 1971, kept confined at Adamjee Cantonment College for a few days before being flown to West Pakistan. He was placed in solitary confinement in Mianwali jail in the Punjab, with no access to newspapers, radio and television. On 9 August, the Pakistan government made it known that he would be placed on trial for waging war against Pakistan and that the trial would commence in camera two days later, on 11 August.

Where in 1968 Bangabandhu had been tried by a special tribunal comprising civilian judges in Dhaka, in Mianwali it was a military tribunal, headed by Brigadier Rahimuddin Khan, which he faced. Bangabandhu refused to recognize the jurisdiction of the court and was not willing to accept A.K. Brohi, the reputed Pakistani lawyer, as his defence counsel.

In November 1971, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was sentenced to death by the military court. By that point, however, Pakistan was in deep trouble in occupied Bangladesh, eventually going down to military defeat in December with the surrender of its armed forces to the allied command of the Mukti Bahini and the Indian army. In Rawalpindi, before handing over the presidency of a rump Pakistan to Z.A. Bhutto, General Yahya Khan asked that he be allowed to execute Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in line with the judgment delivered earlier by the military tribunal. Bhutto rejected the request.

On 22 December 1971, Bangabandhu was freed from solitary confinement and placed under house arrest at a guest house outside Rawalpindi. President Bhutto met him on 23 and 27 December before freeing him in the early hours of 8 January 1972. The Pakistani leader bade Bangabandhu farewell at Chaklala airport.

The Father of the Nation arrived in London on the cold morning of 8 January 1972. Two days later, on 10 January, he flew home to a free, liberated Bangladesh.

He had, throughout his political career, spent 4,682 days in prison. Following the liberation of Bangladesh, he would live for 1,314 days before renegade soldiers of the Bangladesh army would assassinate him and most of his family.

Unauthorized use or reproduction of The Finance Today content for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited.